Intellectual property and pharmaceutical innovation: certain and consistent rules are needed

Today more than ever it can be said that innovation and the intellectual property rights that protect and encourage it are the very heart of world development.

straight edge – December 2, 2019

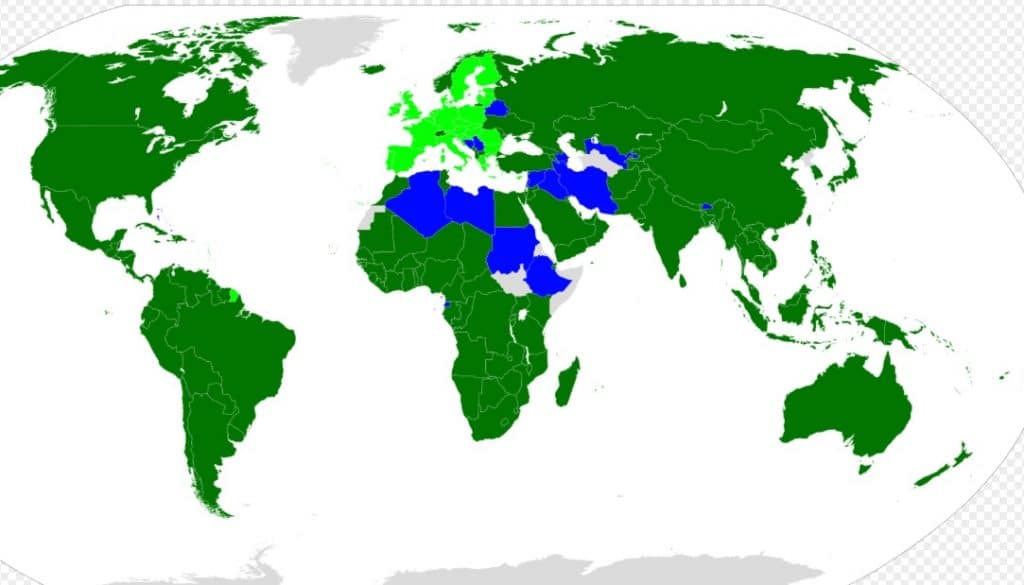

Probably the turning point of this evolution is represented by the TRIPs Agreement (Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights), adopted in Marrakech in 1994  at the same time as the establishment of the World Trade Organization and with which the bloc of the economically more advanced countries at the time, led by the United States, made the liberalization of world trade conditional on compliance by all the countries adhering to the WTO with certain intellectual property rights protection standards: these rights are in fact the most important "added value" of our time and therefore a key element for the competitiveness of businesses.

at the same time as the establishment of the World Trade Organization and with which the bloc of the economically more advanced countries at the time, led by the United States, made the liberalization of world trade conditional on compliance by all the countries adhering to the WTO with certain intellectual property rights protection standards: these rights are in fact the most important "added value" of our time and therefore a key element for the competitiveness of businesses.

What makes the difference is the efficiency of this protection and the coherence of the institutions set up to protect intellectual property with the other provisions of the legal system, so as to give companies the possibility of valorise all the positive externalities deriving from the use of their rights, prohibiting all forms of free riding and parasitic exploitation of their investments. However, while under the first profile Italy is incredibly advanced, thanks to a system of specialized courts and special rules considered best practices at the European level, under the second, our country often suffers from a sort of normative schizophrenia: on the one hand, in fact, it proclaims its intention to encourage research and innovative businesses, on the other, words are contradicted by deeds.

Emblematic of this schizophrenia is the discipline of the so-called therapeutic equivalence, born in the context of health law with the aim of favoring the containment of health expenditure and which allows the Regions to tender drugs based on different active ingredients in a single functional lot, provided they have the same therapeutic indications: without realizing that even the rules relating to NHS expenditure must be framed in the context of pharmaceutical research and therefore respect the exclusive rights that derive from this research - often the result of very significant investments.

Emblematic of this schizophrenia is the discipline of the so-called therapeutic equivalence, born in the context of health law with the aim of favoring the containment of health expenditure and which allows the Regions to tender drugs based on different active ingredients in a single functional lot, provided they have the same therapeutic indications: without realizing that even the rules relating to NHS expenditure must be framed in the context of pharmaceutical research and therefore respect the exclusive rights that derive from this research - often the result of very significant investments.

Upstream of the protection of a patent right there is in fact a research activity which in the pharmaceutical case, in particular, also includes all the subsequent activity that is between the patenting and the moment in which the product will be able to arrive on the market, which is not at all obvious that it will happen.

An approach to this matter that is effective in guaranteeing the patent protection that rightfully belongs to the innovator must therefore take into account the fact that the same technical problem can be solved in a plurality of different ways, giving rise to distinct inventions and patents and therefore different active ingredients, although indicated for the same pathology, cannot be placed on the same level: anyone who has obtained a new drug or a new procedure that does not fall within the scope of patents cannot in fact then claim to have his product have the same position together with that covered by the protected right of others in the context of the same evaluation of "therapeutic equivalence

Therefore, the choice whether to prescribe one or the other must be left to the doctor alone, without it being possible to impose their substitutability except in the case of bioequivalence, which presupposes the identity of the active ingredient and as a rule also that of the method of administration. In this sense the logic of the patent system applied to the pharmaceutical sector converges in the results with the need to protect the safety of patients and the freedom of doctors, to whom the switches from one drug to another cannot be imposed, unless it appears that one can be indifferently taken in place of the other on the basis of adequate scientific/experimental support.

Only in this way is it possible to establish a balance between the interests of the various actors involved (the pharmaceutical patent holder, his competitors, public institutions, doctors and patients), consistent with a correct balancing of the various constitutional rights at stake and with the function that the protection of innovation in the pharmaceutical field must perform in the economic reality and in the "world of life".

Pharmaceutical patent, the thin line between protection and abuse

Altalex – 20/12/2019 by Agnese Iemma

According to a series of surveys, conducted at European level, the pharmaceutical sector can currently be considered one of those most penalized by the Competition and Market Authority, due to the incessant development and use of strategic practices for obtaining patent protection, the  as abstractly lawful, they are in contrast with the dictates of the legislator in the field of industrial property rights, but above all with the antitrust legislation, since most of the time they are used for purely exclusive and anti-competitive purposes.

as abstractly lawful, they are in contrast with the dictates of the legislator in the field of industrial property rights, but above all with the antitrust legislation, since most of the time they are used for purely exclusive and anti-competitive purposes.

In a society like the current one, where, as we also read in the 2009 European Commission report, "innovation is an essential and dynamic component of an open and competitive market economy"[1]; patent protection arises as a manifestation of the principle of free economic initiative which is embodied in the ability of a company to decide autonomously whether or not to protect its inventive activity, through the recognition of an exclusive right aimed at preventing or inhibiting the use, production, marketing, or importation of a product, without the prior consent of the patent holder.

Industrial property rights constitute a considerable corporate resource, especially if one looks at the pharmaceutical market, which represents one of the most important innovative sectors, globally, and is characterized by the dual nature, industrial and therapeutic, of the marketed good.

Although this sector is distinguished by widespread public control, aimed at ensuring, within the limits of pharmaceutical expenditure, the appropriate use of drugs without stifling competitive dynamics, in recent  twenty years, was the most sanctioned by the AGCM, which as also highlighted by the investigations of the European Commission of 2009 and 2019, found that more than the 63% of the agreements concluded between pharmaceutical companies, were to be considered prohibited, pursuant to art. 101 TFEU.

twenty years, was the most sanctioned by the AGCM, which as also highlighted by the investigations of the European Commission of 2009 and 2019, found that more than the 63% of the agreements concluded between pharmaceutical companies, were to be considered prohibited, pursuant to art. 101 TFEU.

And in fact, the spasmodic conquest of the market has led Big Pharma to develop new market strategies, most often based above all on the distorted use of patents which have made the task of distinguishing between licit and illicit, or rather, between protection and abuse, increasingly difficult.

Abuse that occurs whenever the exclusivity obtained from the pharmaceutical company is used in a distorted way, in order to pursue purposes unrelated to those expressly identified by the legislator, thus losing its pro-competitive function and acquiring an excluding purpose in contrast.

The ability of the patent to transform itself into an anti-competitive tool is not only known in the pharmaceutical sector but is found in all economic sectors, however it is precisely in this that it causes greater concern, because it is capable of significantly affecting not only the rules that regulate the market and competition, but more specifically, a fundamental right for human life, such as the right to health.

In this context, the Roche/Genentech/Novartis case is placed, in the last few days once again in the spotlight, due to the cyclone that hit the top management of the Italian Medicines Agency, under investigation by the Court of Auditors for having caused an alleged tax damage of around 200 million euros to the National Health Service.

In fact, some AIFA executives were investigated by the Lazio Court of Auditors, accused of having managed to limit the prescriptions of the drug Avastin over the years in favor of the more expensive Lucentis, causing damage to the treasury, currently quantified at 200 million euros.

In this regard, already on February 27, 2014, the Antitrust had fined Roche and Novartis for 180 million euros, due to a cartel that had influenced the sales of the main products intended for eye care.

According to the AGCM, the two companies had agreed to spread false news among doctors in order to promote, for the treatment of ophthalmic diseases, the sale of Lucentis, a drug covered by the National Health System, with an indicative cost of €900, instead of Avastin, by far cheaper, which costs around €80.

In 2004, in fact, the multinational Roche, or rather, its subsidiary Genentech, developed an anticancer drug called Bevacizumab, which in 2005 even without a marketing authorization, which was never requested, was approved, marketed and included by AIFA in the list for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration, with the name of Avastin.

In 2007, starting from Bevacizumab, Genentech itself then developed a second drug, Lucentis, incredibly more expensive than Avastin, which, however, obtaining the marketing authorization, AIC, for the treatment of macular degeneration related to senile age, gradually replaced the latter in the list of drugs available at the total expense of the NHS.

In 2007, starting from Bevacizumab, Genentech itself then developed a second drug, Lucentis, incredibly more expensive than Avastin, which, however, obtaining the marketing authorization, AIC, for the treatment of macular degeneration related to senile age, gradually replaced the latter in the list of drugs available at the total expense of the NHS.

The failure to request authorization to market Avastin, however, led the Antitrust to believe that the strategy adopted by Genentech had solely and exclusively economic purposes, to the limit of the provisions of the antitrust legislation, generated by the interconnection between Roche, Novartis and Genentech, the latter controlled by Roche, in turn, for more than 30% owned by Novartis.[2]

Further investigations later revealed that the exclusion of Avastin from the list of drugs available at the total expense of the NHS was nothing more than the result of an agreement between the parent companies Roche and Novartis, aimed precisely at sabotaging the sale of the latter, presenting it as more dangerous than Lucentis and thus influencing doctors, health services and above all the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA).

The agreement, developed starting from this strategy of artificial "differentiation" of the two main drugs, used for the same pathologies, which precisely had the sole purpose of limiting the prescription of Avastin and favoring that of Lucentis, so as to obtain greater profits, could not fail to be considered elusive of the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements, pursuant to art. 101 TFEU, by the EU Court of Justice, called into question by the Italian Council of State, following the appeal by Roche and Novartis, against the fine of around 180 million euros imposed by the Antitrust.

This ruling by the Court of Justice of the EU at the basis of the very recent investigations carried out by the Court of Auditors of Lazio, can only authorize, pending further developments on the accusations made against the former director general of AIFA and the members of the technical-scientific commission, who decided on the "unjustified limitations on the reimbursement" of Avastin, a conclusive consideration.

This ruling by the Court of Justice of the EU at the basis of the very recent investigations carried out by the Court of Auditors of Lazio, can only authorize, pending further developments on the accusations made against the former director general of AIFA and the members of the technical-scientific commission, who decided on the "unjustified limitations on the reimbursement" of Avastin, a conclusive consideration.

“Intellectual property rights”, as can be seen from the aforementioned 2009 European Commission report, “foster dynamic competition and encourage companies to invest in the development of new or improved products and processes”, while “competition works by pushing companies to innovate”.

"For this reason, both intellectual property rights and competition are necessary to promote innovation and ensure that it is exploited in a competitive way" however it cannot be denied that greater attention to the rules that regulate this close interconnection, between patent protection and antitrust law, is to be hoped for.

Indeed, today to delve into the matter of pharmaceutical patent protection, without dealing at the same time with antitrust law, means not fully understanding the subject that is being addressed and perhaps this is precisely why over the years, pharmaceutical companies have easily managed to abuse their patent rights.

The Roch/Genentech/Novartis case certainly represents an example of the increasingly stringent need to guarantee, perhaps through the preparation of new tools, the effective implementation of the rules that help protect entrepreneurs and competition, but more specifically consumers, who, especially in this sector, cannot fail to be guaranteed the purchase of medicines at competitive prices and therefore the effective enjoyment and protection of the right to health, pursuant to art. 32 of the Constitutional Charter.

It is certainly not easy to state with certainty what the solution might be that opposes the adoption of such exclusionary mechanisms, however a more severe application of the rules governing the matter must be deemed necessary.

>> Read also on the matter Registered trademark: the complete guide (procedure, formalities, conditions and costs for registration).